All My Lovers

ALL MY LOVERS

Solo show at Slag Gallery, explore the exhibition in 3D Profile by Seph Rodney on New York Times

April 20, 2020 to June 20, 2020

Slag Gallery is pleased to present All My Lovers, a new body of mixed media paintings by artist Naomi Safran-Hon. The exhibition is Safran-Hon’s fourth solo show with Slag Gallery and inaugurates the gallery’s new space in Chelsea, Manhattan.

Two years from her last exhibition with Slag Gallery, All My Lovers represents an evolutionary step in Naomi Safran-Hon’s practice and the artist’s exploration of the liminal space between content and formalism. She continues her interrogation of the concept of home as both physical site and familiar locus for the conflict between myth and truth, but has expanded her practice, pushing against the boundaries of painting and incorporating the sculptural into her work, enabling herself to more intensely investigate her subject matter.

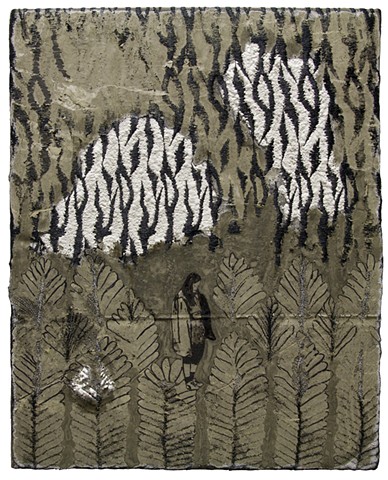

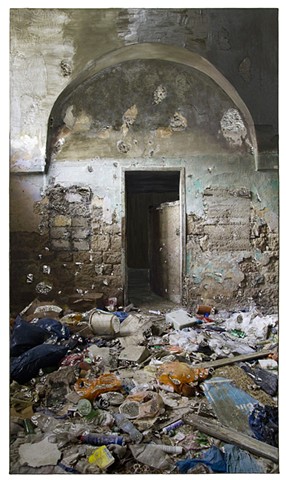

With its depiction of only a dilapidated interior wall, the work “Taking Me for Granted” may exemplify Safran-Hon’s oeuvre more than any other work in the exhibition, yet the new juxtapositions of different materials across its surface signal an additional stratum of complexity for the artist’s work. Safran-Hon creates her paintings with a process that begins with her documentary-like photographs of the interiors of abandoned buildings in the Wadi Salib neighborhood of Haifa, Israel, her hometown. She affixes one or more of her photographic prints to a canvas, then uses a razor to cut through the print and canvas along the details of architecture and light in the photograph. Behind the gaps and voids she opens, she then stitches a layer of porous textile, typically lace, and through which she uses a painter’s knife or trowel to push cement so that it seeps through the painterly plain from behind. This process literalizes the entropic decay of the concrete walls, halls, and doorways of the former living spaces in Safran-Hon’s photographs, but in so doing, plumbs the precarious line between fiction and truth, myth and reality: The representative objectivity of photography and impressionist nature of painting become suffused within one another. In “Taking Me for Granted,” the artist takes an additional step to manifest this tension by subtly painting over and beyond the lines and surfaces of her photographed interiors, an act that further deceives the viewer’s eye and elevates the photograph beyond the pictorial portrayal of its subject.

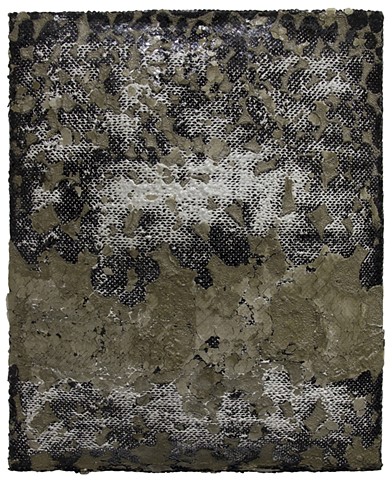

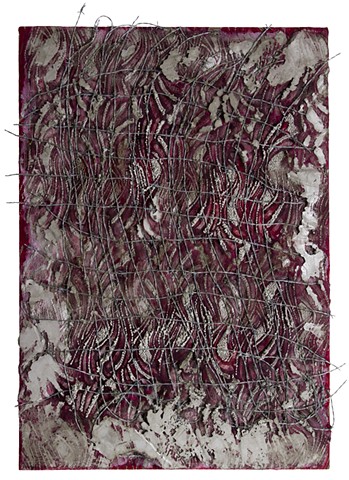

By revealing their fragility of building materials in her photographed interiors, Safran-Hon elucidates the assumptions that underlie domestic spaces, showing us what we may, in fact, take for granted. While the shelter that a home provides is a necessity for basic well-being, the security it provides is an illusion, for it is not only the site of the emotional nourishment that determines our lives’ outcomes, but the trauma that does so as well, a dialectical pattern that is born out in the artist’s cement and lace. With the work “Night Plumber,” Safran-Hon focuses on an essential aspect of a home; just as she concentrates her painterly frame on a single wall in “Taking Me for Granted,” here the artist further considers what may hide within the familiarity of one’s dwelling. The work’s depiction of water pipes is an additional parsing of what comprises a domestic space; they are conduits for the substances of life’s most basic processes. As a diptych, “Night Plumber” not only combines the artist’s antithetical media of lace and cement, and photography and paint, but incorporates sculptural elements that further manipulate the photographic depictions at the root of Safran-Hon’s process, increasing the tactility of her concept and integrating representation and object, formalism and content.

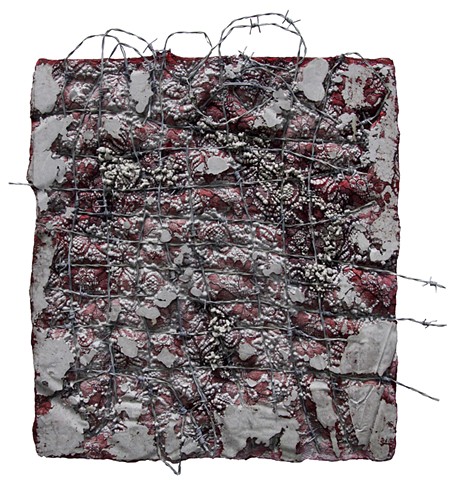

The artist's “The Pattern of My Surrender” best evidences the intensification of conceptual rigor in Safran-Hon’s practice. On a layer of wine-colored lace stretched on a frame and infused and distended with cement, the artist has woven a grid of barbed wire, yet the steel’s innate properties work against the iterative squares of the weave: The metal has a memory, and it flexes and strains against the grid's right angles. The work includes no photographic material, but the steel itself supersedes the representative property of a photograph, and just as Safran-Hon’s use of cement and lace effectuates dialectical themes of masculine and feminine and public and domestic, the act of transforming barbed wire into a woven pattern is an antithetical subversion of its intended purpose. Like cement, barbed wire is a symbol of its intended application: They both synthesize and signify power while lace acts as their foil.

In Safran-Hon’s works, Wadi Salib is the site through which she commences her exploration of truth and fiction, facts and subjectivity. It is a contested site in the political mythology of Israel and Palestine, and remains neither inhabited nor demolished. Factuality, itself a formal concept, and meaning, itself subjective, are fundamentally both interwoven and at odds, and in this artist’s new paintings, she dissolves them into one another. This collapse of formalism into memory and history, however, is neither amoral nor nihilistic in its dissolving of fact and fiction. In a time when truth itself has become more political than ever, Safran-Hon’s meditations seem more revelatory than truth itself.

- Christian Holland